CBT-Inspired Exercises

- jessicaaqian

- Aug 8, 2024

- 7 min read

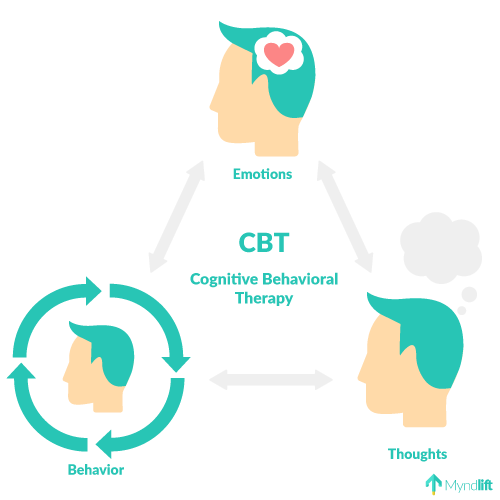

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps people learn how to identify and change destructive or disturbing thought patterns that have a negative influence on behaviour and emotions.

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is an umbrella term for a wide array of cognitive and behavioural oriented exercises and techniques that mental health professionals utilise to alleviate symptoms in various mental health conditions. Whilst most commonly used in clinical settings, some of the skills and exercises found in CBT can be useful in and applied to daily life. Before delving into these exercises and skills, let us first elaborate two key definitions that will help you better understand how to use this guide.

The cognition (i.e., cognitive) aspect refers to our thoughts about, attention to, memories relating to, perceptions regarding, and interpretations of various situations or occurrences in our lives; the underlying belief from this perspective is that our experiences in the world are due to various cognitive activities which occur in the brain.

The behaviour (i.e., behavioural) aspect focuses on observable and measurable actions that we perform in daily life, and are essential to the way we navigate the world; this perspective views behaviours as acquired or learned responses from past experiences. Taken together, traditional CBT draws influences from the cognitive and behavioural perspectives to introduce a variety of techniques which focus on eradicating the perpetuating or maintaining factors which allow problems or distress to persist. In a clinical setting, CBT relies on multiple sources of information to direct and inform the clinician on suitable approaches. We have simplified the exercises to maintain only the core of particular techniques.

At this point, it needs to be made clear that the exercises and skills found in this guide are not a substitution or replacement for formal mental health support and you should seek help from a mental health professional if you are experiencing mental distress. We hope to achieve with this guide the imparting of CBT inspired exercises and skills that are easy to apply, require little to no advanced understanding of CBT's principles, and do not need professional guidance to utilise. Here are two simple to use CBT inspired exercises to boost your psychological wellbeing

Cognitive Restructuring

This exercise's primary goal is to better understand and evaluate our various thoughts in a non-judgemental and objective manner. Cognitive restructuring relies on identifying the roots of our negative thoughts, emotions, and identifies connections between them; we then search for possible alternate narratives that could be present, which help relieve the distress from these thoughts.

There are a variety of techniques that can be applied to such a process, but some require more guidance than others, and we have selected those which can be done without much external support as listed below:

1) Thought Distancing The idea underlying creating psychological “space” from our thinking it so that we can view it from a third-party perspective and in a more objective manner. In doing so, we can better dismantle or unpack our thoughts in a non-defensive way, allowing for change to occur more effectively. To distance ourselves from our thoughts, consider writing certain negative or distressful ones out on a piece of paper, record them digitally on your phone’s or computer’s “notepad”, or imagine your various thoughts as flashing images within your life similar to television advertisements or computer prompts.

2) Thought Evaluation Here are several helpful steps to evaluate negative and distressing thoughts and resulting emotions you may have. Some prompts labelled third-party are best used in consultation with someone else to ensure objectivity in the response.

Begin by asking yourself how much on a scale of 0% to 100% do you believe in the thought.

Identify various emotions you feel due to this thought and rate them from 0 to 10 on how substantial these feelings are.

Identify useful ‘evidence’ (i.e., instances or experiences) in your life that supports or disproves this thought.

What would you tell someone else if they mentioned this thought and the resulting emotion to you?

What have been the effects of your thought so far? (third party)

What would others tell you if you shared this thought and the resulting emotion with them? (third party)

3) Reframing Often, there are many possible interpretations to a particular thought, but during a state of distress or when we are feeling negative, sufficient consideration may not be given to these alternate possibilities. The following prompts can help you challenge and possibly rebalance these negative thoughts and their resultant emotions we may have from time to time; prompts labelled third-party are best used with another person.

What are some other ways you can view this thought and the resulting emotion?

Is there a more balanced, less extreme or negative alternative?

Is there any evidence that can be found for alternate explanations?

If you wanted to feel differently about this thought and/or its resulting emotion, how would your thinking have to change?x`

Is there anything more to this thought and the emotions that it leads to than you are currently seeing? (third party)

What would others tell you if you shared this thought and its resulting emotion with them? (third party)

Common Cognitive Distortions

All-or-Nothing thinking – Black and white perspectives to various circumstances in life. Lacking a middle ground and categorizing things as only good or bad (e.g., I need to be perfect if not I’m a failure).

Overgeneralisation – Using one example or occurrence and view it as the main pattern of how situations usually play out (e.g., Failing to score well on an exam as an indicator of a student being stupid or useless).

Ignoring/Disqualifying the positive – Not acknowledging positive experiences or occurrences, choosing to reject them as being untrue (e.g,. Not accepting compliments or attributing these compliments to others being polite or nice).

Mental Filter – Choosing to only focus on negative information and ignore other positive evidence (e.g., Focusing on one mistake amongst many other correct answers on a quiz).

Mind Reading – The assumption that we know what others are thinking without adequate evidence to support the conclusion drawn (e.g., Thinking others are laughing at you for eating alone).

Fortune Telling – Coming to conclusions or making predictions with limited evidence or gut feelings (e.g., Assuming you will never find love based on the fact you have never been in a relationship)

Catastrophising – Exaggerating the meaning, possibility, importance, significance, or likelihood of something that has happened or will happen (e.g., Feeling dizzy and thinking you are going to die).

Emotional Reasoning – Using feelings as a basis for justification instead of facts (e.g., I feel useless therefore I must be useless).

Should Statements – Constantly creating unrealistic, rigid, or unreasonable expectations or rules for yourself or imposing them on others (e.g., I should be able to do something or they should be able to do something)

Labelling – Using labels on yourself or others based on your own beliefs, values, and normally based on limited evidence (e.g., Calling yourself stupid for not being able to complete a certain assignment).

Self-Blame – Taking full responsibility and blame for something that is not your fault or only partially your fault, and at times, without any strong evidence that it is your fault (e.g., If only I was more fun, people around me would not be so bored).

Scanning – Looking out for and finding things that you are fearful of (e.g., Constantly finding threats or potential dangers in the environment around you).

Behavioural Activation

Underlying this exercise is the belief that by engaging in activities and behaviours that result in positive feelings such as enjoyment or happiness, we can create a psychological buffer from the impact of negative stressors and emotions in our daily lives. By keeping track of our day to day activities, and identifying how they make us feel, we can choose the ones that lead to the highest level of happiness or positivity to be used whenever we begin to feel down, hence the name behavioural activation.

Here are some steps by which you can use to perform this activity:

1) Keep Track of Your Daily Activities For A Week Or Two This exercise may take some practice, and you should decide how you want to monitor this process. For example, you could split your day into morning, afternoon, evening, night; or another combination based on a timeline that suits you best. The activities captured should be anything you do during the day, such as hanging out with friends, going to school, doing your homework, etc.

2) While Tracking Your Activities, Also List Out How They Make You Feel A convenient scale to use would be (0 = very sad and 10 = very happy). Adding or using specific mood descriptors can allow you to clearly remember what these engagements made you feel and give more depth to the quality of information recorded. Adding dimensions that can be rated on a scale of 1 to 10, such as levels of achievement, social connectedness, and personal enjoyment can also help you better learn what works for you

Comments